Image source: 🔗 https://pxhere.com/fr/photo/954900 | |

| Theme | Does the feeling of injustice authorize recourse to illegality? |

| Animation | UPP ALDERAN |

| Date and times | Tuesday, September 17, 2024 from 8:30 p.m. to 10:30 p.m. |

| Keywords | café, debate, feeling, injustice, law, illegality, fairness, justice, human rights, limits, allow |

| Information | For more details on how the event works, see the page on the WEB philo café. |

Introduction▲

This WEB café philo is an “online”, “on the web” café philo where participants meet in a Zoom meeting to debate on a topic known in advance. It is the first online café philo animated by the UPP ALDERAN association because other philosophy cafes exist in person, like Victor Schoelcher philosophy café in Toulouse.

The topic of today’s debate is the feeling of injustice and the use of illegality:

Does the feeling of injustice authorize recourse to illegality?

WEB Café philo, UPP ALDERAN, Tuesday September 17, 2024.

Yes or no, and why? I share some answers or ideas that I have retained with more or less precision.

Note: This article mentions elements of reflection from the debate with varying degrees of precision and does not transcribe the entire debate point by point. It is therefore not intended to be exhaustive in terms of its content but invites further reflection on the subject.

1. The feeling of injustice▲

1.1. The subjectivity of the feeling of injustice▲

The expression used raises the question of subjectivity, of the real nature of injustice. Indeed, it is not because one feels injustice that it is founded.

1.2. The origin of the feeling of injustice▲

Why do we feel this way? What is its origin, its source? What makes us feel an incongruent state inside ourselves, which we recognize and call the feeling of injustice?

1.3. The reaction time to render justice▲

With the feeling of injustice, we realize that we want to obtain justice immediately, without taking a step back, under the influence of emotion, of feeling. Is it fair to render justice immediately? The time it takes to render justice is not the same as the time it takes to obtain justice.

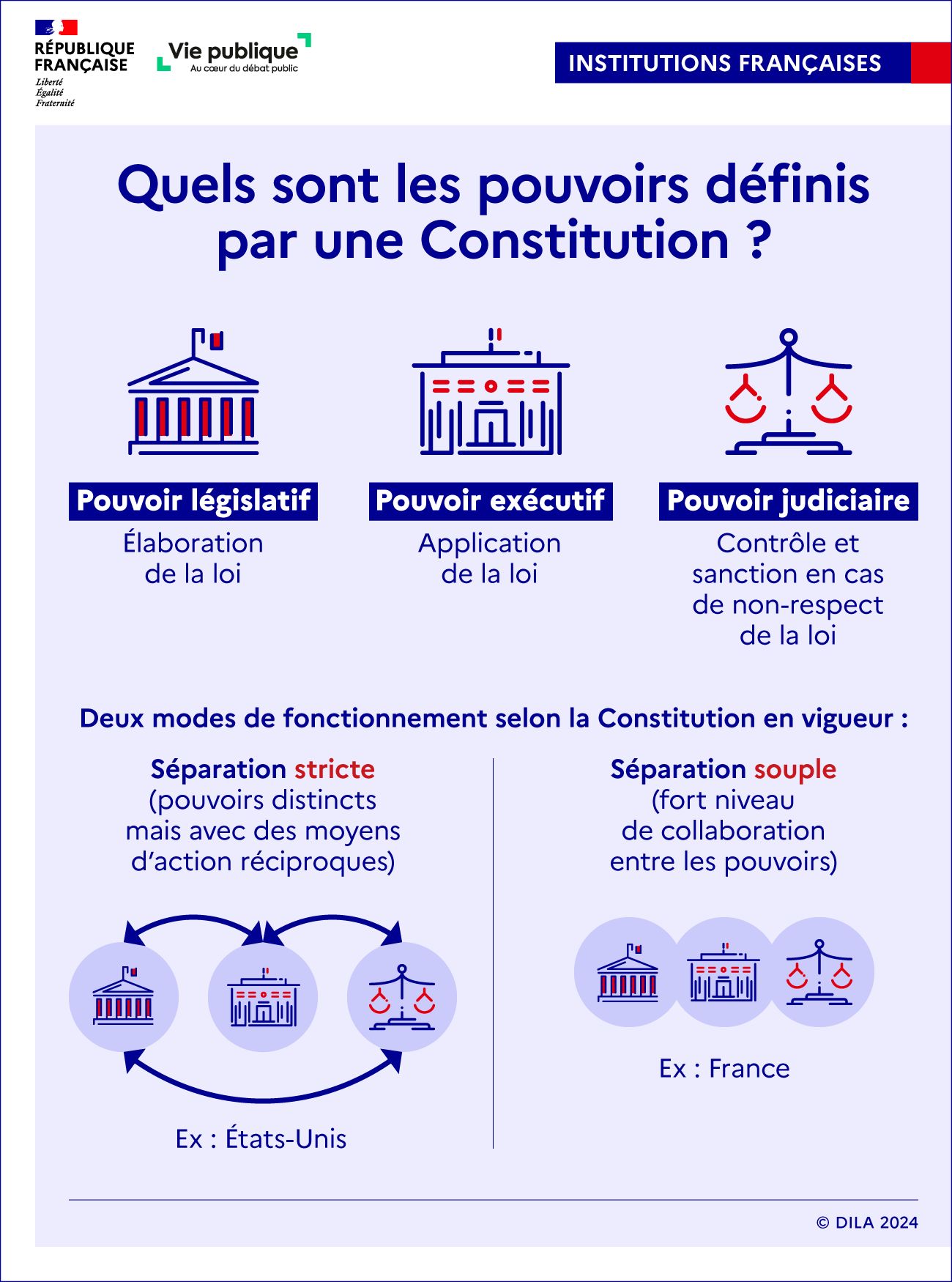

2. Justice and law, two of the powers▲

On the importance of the separation of powers.

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state power (usually law-making, adjudication, and execution) and requires these operations of government to be conceptually and institutionally distinguishable and articulated, thereby maintaining the integrity of each. To put this model into practice, government is divided into structurally independent branches to perform various functions (most often a legislature, a judiciary and an administration, sometimes known as the trias politica). When each function is allocated strictly to one branch, a government is described as having a high degree of separation; whereas, when one person or branch plays a significant part in the exercise of more than one function, this represents a fusion of powers.

Source: Wikipedia EN, Separation of powers, 05/11/2024.

3. Justice▲

I share three definitions of justice according to:

- Wiktionary, the free dictionary,

- Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia,

- Larousse, an online French dictionary service.

You can also take a look at the website of the Ministry of Justice in France to learn more about its organization, its role and its missions in France.

3.1. Definition of justice according to Wiktionary▲

justice (countable and uncountable, plural justices)

- The state or characteristic of being just or fair.

- The ideal of fairness, impartiality, etc., especially with regard to the punishment of wrongdoing.

- Judgment and punishment of a party who has allegedly wronged another.

- The civil power dealing with law.

- A title given to judges of certain courts; capitalized when placed before a name.

- Correctness, conforming to reality or rules.

Judgment and punishment of a party who has allegedly wronged another.

Source: justice, Wiktionary (6 points), 17/11/2024.

3.2. Definition of justice according to Wikipedia▲

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the concept that individuals are to be treated in a manner that is equitable and fair

A society in which justice has been achieved would be one in which individuals receive what they “deserve”. The interpretation of what “deserve” means draws on a variety of fields and philosophical branches including ethics, rationality, law, religion, equity and fairness. The state may be said to pursue justice by operating courts and enforcing their rulings.

Source: Justice, Wikipedia EN, 17/11/2024.

3.3. Definition of justice according to Larousse▲

A personal translation

Justice brings together universal principles that require respect for the law and fairness. These principles are inspired by habeas corpus (1679), which aimed to guarantee individual freedom in the face of arbitrariness. In this context, every accused person has the right to a trial and to be defended by a lawyer. The debates at the trial must be adversarial and the defense, like the prosecution, must have access to the file that explains the charges against the accused person. State representatives must be impartial. In France, offences (theft, drug trafficking, etc.) are punishable by the criminal court and the maximum penalties incurred are five years. Crimes (homicide, physical violence and rape, terrorism, etc.) are judged by a assize court, composed of three professional magistrates and nine jurors. The court of appeal, seized by the defense or the prosecution, can confirm or overturn a judgment. The court of cassation can overturn a judgment, but only if the rules of procedure have not been respected. Crimes against humanity are imprescriptible. Fines, in particular for traffic violations, are notified by a police court. The industrial tribunal is competent for disputes that arise in the world of work. Juvenile justice is rendered by a special jurisdiction. Depending on the seriousness of the acts, minors are judged by the juvenile judge, by a juvenile court or by the juvenile assize court.

Source: justice, Larousse, a French dictionary, 17/11/2024.

3.4. During the debate▲

- The role of justice was discussed.

- Check the reality of the facts.

- Justice is done with hindsight, not on the spur of the moment, for the sake of objectivity. It can take a long time for justice to be done.

- Justice must be emancipated as power (separation).

- The concepts of justice and law must be distinguished.

- Justice must punish and condemn the guilty. But what about restorative, rehabilitative justice?

4. The verb ‘to authorize’▲

Between “having the right”, “having the authorization”, “deciding on one’s own to do”, “allowing oneself to do it”, “breaking the law”, “exceeding the limits”, the nuances can be tenuous depending on the circumstances. The expression “authorizing recourse” raises the question of what it is possible to do individually in a society where rules have been established. What to do when one finds oneself at the limits provided for by the law? To what extent can one grant oneself the right to become an outlaw?

5. Law and illegality▲

5.1. Definition of law▲

5.1.1. Definition of law according to Wiktionary▲

law (countable and uncountable, plural laws)

- (usually with “the”) The body of binding rules and regulations, customs and standards established in a community by its legislative and judicial authorities.

- A binding regulation or custom established in a community in this way.

- (more generally) A rule (7 points).

- The control and order brought about by the observance of such rules.

(…following…)

Source: law, Wiktionary (12 points), 17/11/2024.

5.1.2. Definition of law according to Wikipedia▲

A statute is a formal written enactment of a legislative body, a stage in the process of legislation. Typically, statutes command or prohibit something, or declare policy. Statutes are laws made by legislative bodies; they are distinguished from case law or precedent, which is decided by courts, regulations issued by government agencies, and oral or customary law. Statutes may originate with the legislative body of a country, state or province, county, or municipality.

The word “statute” is derived from the late Latin word “statutum”, which means ‘law’, ‘decree’.

Source : Loi, Wikipédia EN, 17/11/2024.

5.1.3. Definition of law according to Larousse▲

A personal translation of the definition

In the broad sense, the law (cf. Larousse dictionary) is the set of customary and written standards in force whose binding nature ensures a minimum of social cohesion (in this sense, the “law” covers the notion of “right”).

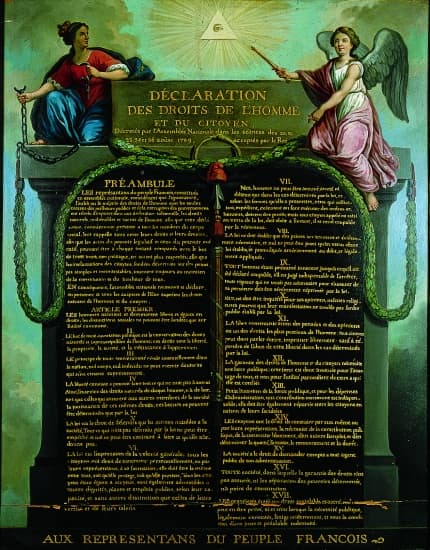

For a long time, the law was associated with the idea of divinity: in Antiquity, in Greece or in the Rome of kings, it was in the name of the gods that individuals issued standards valid for the entire social body. “Law and religion were one” states the historian Fustel de Coulanges in La Cité antique (1854). Until the 18th century, the Ancien Régime in France was a monarchy “by divine right”. The concept of law as an expression of the popular will was developed by Jean-Jacques Rousseau during the Age of Enlightenment. From the French Revolution onwards, it became one of the fundamental principles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789), which established an essential part of French law and democratic regimes. Article 6 of the 1789 Declaration stipulates that “the law is the expression of the general will“, and adds that “all citizens have the right to contribute personally or through their representatives to its formation”. In its strict sense, “law” therefore designates the standards that emanate from Parliament, which is the elected representative of the entire people.

The same article establishes the general and obligatory character of the law: “it must be the same for all, whether it protects or punishes.”

Source : loi (law), Larousse, a French dictionary, 17/11/2024.

5.2. How to get justice▲

5.2.1. Revenge▲

Revenge is defined as committing a harmful action against a person or group in response to a grievance, be it real or perceived. Vengeful forms of justice, such as primitive justice or retributive justice, are often differentiated from more formal and refined forms of justice such as distributive justice or restorative justice.

Revenge, Wikipedia EN, 17/11/2024.

5.2.2. Blood feud▲

A blood feud is a feud with a cycle of retaliatory violence, with the relatives or associates of someone who has been killed or otherwise wronged or dishonored seeking vengeance by killing or otherwise physically punishing the culprits or their relatives. In the English-speaking world, the Italian word vendetta is used to mean a blood feud; in Italian, however, it simply means (personal) ‘vengeance’ or ‘revenge’, originating from the Latin vindicta (vengeance), while the word faida would be more appropriate for a blood feud. In the English-speaking world, “vendetta” is sometimes extended to mean any other long-standing feud, not necessarily involving bloodshed. Sometimes it is not mutual, but rather refers to a prolonged series of hostile acts waged by one person against another without reciprocation.

Blood feud, Wikipedia EN, 17/11/2024.

5.3. How to do justice with the law▲

Questions raised during the debate:

- Are the judiciary and the legislative powers clearly separated?

- Does the application of the law allow for a fair trial, objective justice?

5.3.1. Eye for an eye▲

“An eye for an eye” (Biblical Hebrew: עַיִן תַּחַת עַיִן, ʿayīn taḥaṯ ʿayīn) is a commandment found in the Book of Exodus 21:23–27 expressing the principle of reciprocal justice measure for measure. The earliest known use of the principle appears in the Code of Hammurabi, which predates the writing of the Hebrew Bible but not necessarily oral traditions.

The law of exact retaliation (Latin: lex talionis), or reciprocal justice, bears the same principle that a person who has injured another person is to be penalized to a similar degree by the injured party. In softer interpretations, it means the victim receives the [estimated] value of the injury in compensation. The intent behind the principle was to restrict compensation to the value of the loss.

Source: Eye for an eye, Wikipedia EN, 17/11/2024.

5.3.2. Salic law▲

The Salic law (/ˈsælɪk/ or /ˈseɪlɪk/; Latin: Lex salica), also called the Salian law, was the ancient Frankish civil law code compiled around AD 500 by the first Frankish King, Clovis. The written text is in Late Latin and contains some of the earliest known instances of Old Dutch. It remained the basis of Frankish law throughout the early Medieval period, and influenced future European legal systems. The best-known tenet of the old law is the principle of exclusion of women from inheritance of thrones, fiefs, and other property. The Salic laws were arbitrated by a committee appointed and empowered by the King of the Franks. Dozens of manuscripts dating from the sixth to eighth centuries and three emendations as late as the ninth century have survived.

Salic law provided written codification of both civil law, such as the statutes governing inheritance, and criminal law, such as the punishment for murder. Although it was originally intended as the law of the Franks, it has had a formative influence on the tradition of statute law that extended to modern history in much of Europe, especially in the German states and Austria-Hungary in Central Europe, the Low Countries in Western Europe, Balkan kingdoms in Southeastern Europe, and parts of Italy and Spain in Southern Europe. Its use of agnatic succession governed the succession of kings in kingdoms such as France and Italy.

Source: Salic law, Wikipedia EN, 17/11/2024.

5.3.3. Magna Carta▲

Magna Carta Libertatum (Medieval Latin for “Great Charter of Freedoms”), commonly called Magna Carta or sometimes Magna Charta (“Great Charter”), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal Stephen Langton, to make peace between the unpopular king and a group of rebel barons, it promised the protection of church rights, protection for the barons from illegal imprisonment, access to swift and impartial justice, and limitations on feudal payments to the Crown, to be implemented through a council of 25 barons. Neither side stood by their commitments, and the charter was annulled by Pope Innocent III, leading to the First Barons’ War.

Source: Magna Carta, Wikipedia EN, 17/11/2024.

5.4. During the debate▲

I have noted three concepts that I wish to highlight: Rechtsstaat (lit. “state of law”, the balance of power and civil disobedience.

5.4.1. Rechtsstaat▲

Rechtsstaat (German: [ˈʁɛçt͡sˌʃtaːt] ⓘ; lit. “state of law”; “legal state”) is a doctrine in continental European legal thinking, originating in German jurisprudence. It can be translated into English as “rule of law”, alternatively “legal state”, state of law, “state of justice”, or “state based on justice and integrity”. It means that everyone is subjected to the law, especially governments.

A Rechtsstaat is a constitutional state in which the exercise of governmental power is constrained by the law. It is closely related to “constitutionalism” which is often tied to the Anglo-American concept of the rule of law, but differs from it in also emphasizing what is just (i.e., a concept of moral rightness based on ethics, rationality, law, natural law, religion, or equity). Thus it is the opposite of Obrigkeitsstaat or Nichtrechtsstaat (a state based on the arbitrary use of power), and of Unrechtsstaat (a non-Rechtsstaat with the capacity to become one after a period of historical development).

5.4.2. Balance of power▲

The expression ‘balance of power’ was cited several times during the debate. Here is its definition according to the French Wikipedia, with my personal translation:

A balance of power is a relationship of conflict between several parties who oppose their powers, or in a more literal sense their forces, whether this force is physical, psychological, economic, political, religious, military…

If the parties involved in the balance of power have unequal power, we distinguish the dominant party and the dominated party: then the Might makes right applies, in other words the arbitrariness of power. The use of such power is generally called violence, in a physical, moral or social (or even ecological) sense.

5.4.3. Civil disobedience▲

Civil disobedience is the active, and professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called “civil”. Hence, civil disobedience is sometimes equated with peaceful protests or nonviolent resistance. Henry David Thoreau‘s essay Resistance to Civil Government, published posthumously as Civil Disobedience, popularized the term in the US, although the concept itself has been practiced longer before.

Civil disobedience, Wikipedia EN, 17/11/2024.

6. Examples where illegality was used▲

6.1. The abolition of slavery▲

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. Under the actions of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, chattel slavery has been abolished across Japan since 1590, though other forms of forced labour were used during World War II. The first and only country to self-liberate from slavery was actually a former French colony, Haiti, as a result of the Revolution of 1791–1804. The British abolitionist movement began in the late 18th century, and the 1772 Somersett case established that slavery did not exist in English law. In 1807, the slave trade was made illegal throughout the British Empire, though existing slaves in British colonies were not liberated until the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. Vermont was the first state in America to abolish slavery in 1777. By 1804, the rest of the northern states had abolished slavery but it remained legal in southern states. By 1808, the United States outlawed the importation of slaves but did not ban slavery —except as a punishment— until 1865.

6.2. Suffragette actions for women’s right to vote▲

A suffragette was a member of an activist women’s organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner “Votes for Women”, fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members of the British Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), a women-only movement founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst, which engaged in direct action and civil disobedience. In 1906, a reporter writing in the Daily Mail coined the term suffragette for the WSPU, derived from suffragist (any person advocating for voting rights), in order to belittle the women advocating women’s suffrage. The militants embraced the new name, even adopting it for use as the title of the newspaper published by the WSPU.

To be a suffragist or a suffragette?

6.3. The Manifesto of the 343 and the law for IVG in France▲

The Manifesto of the 343 (French: Manifeste des 343) is a French petition penned by Simone de Beauvoir, and signed by 343 women, all publicly declaring that they had had an illegal abortion. The manifesto was published under the title, “Un appel de 343 femmes” (‘an appeal by 343 women’), on 5 April 1971, in issue 334 of Le Nouvel Observateur, a social democratic French weekly magazine. The piece was the sole topic on the magazine cover. At the time abortion was illegal in France, and by admitting publicly to having aborted, women exposed themselves to criminal prosecution.

The manifesto called for the legalization of abortion and free access to contraception. It paved the way for the “Veil Act” — named for Health Minister Simone Veil — which repealed the penalty for voluntarily terminating a pregnancy. The law was passed in December 1974 and January 1975, and afforded women the ability to abort during the first ten weeks (later extended to fourteen weeks)

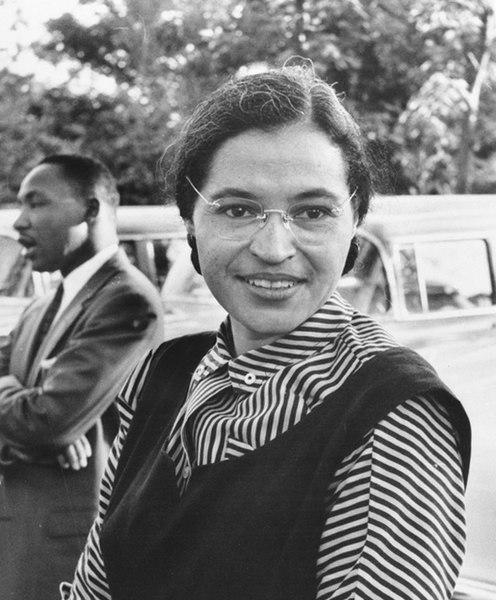

6.4. Rosa Parks and the opposition to a racist law▲

Rosa Parks was an American activist in the civil rights movement, best known for her pivotal role in the Montgomery bus boycott. The United States Congress has honored her as “the first lady of civil rights” and “the mother of the freedom movement”.

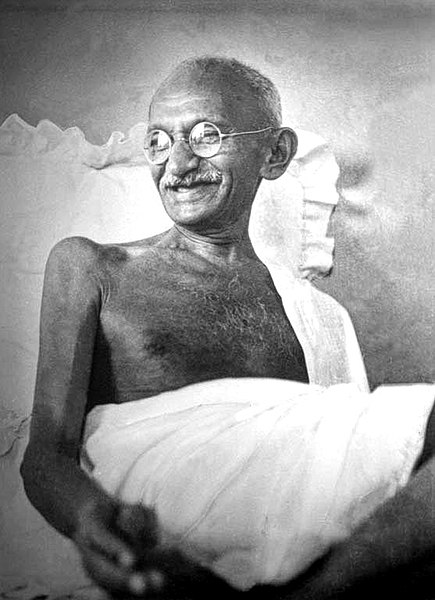

6.5. Gandhi and the decolonization of India▲

The Indian Independence Movement was a series of historic events in South Asia with the ultimate aim of ending British colonial rule. It lasted until 1947, when the Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed.

The stages of the independence struggle in the 1920s were characterised by the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi and Congress’s adoption of Gandhi’s policy of non-violence and civil disobedience.

6.6. Whistleblowers▲

Whistleblower protection: a challenge for democracy?

A whistleblower is a person who reports facts that seriously harm the public interest. In France, since 2016 (the “Sapin II” law), the whistleblower has benefited from a protective status against the risks incurred by his revelations.

6.7. Struggles for human rights▲

Never in history have human rights been obtained because the dominant people “understood” and gave them to the oppressed people after a beneficial awareness. Human rights have always been obtained through hard struggle. And once acquired, we must always continue to fight to keep them because they are not definitively so. And unfortunately, we can thus make the following observation:

Apartheid was legal. The Holocaust was legal. Slavery was legal. Colonization was legal. Legality is a matter of power, not justice.

Primary source: quote often read on the web.

Sonia Kanclerski, Pause-café chez Sonia, 17/11/2024.

Conclusion▲

The question “Does the feeling of injustice authorize the use of illegality?” leads to a permanent questioning. We cannot express a systemic answer because of the absence of the framework in which the action that gave rise to the feeling of injustice occurred: for this question, we thus note an obligation to contextualize. We can therefore only answer yes or no on a case-by-case basis.

This first WEB café philo reminded me of another café philo that I had attended in person in Toulouse and which had left its mark on me on the theme of (non-)violence: